Strength training consists of following a program that increases an individual’s ability to produce muscular effort against resistance for the purpose of displacing it. This resistance is almost always external, like when we lift an Olympic bar, but it can also be internal resistance, like when we lift our body when performing a pull-up.

When training strength we must follow a logical progression. To do this we must first determine the athlete’s current strength level and then construct a program that is efficient for the purpose of causing an increase in strength for that athlete.

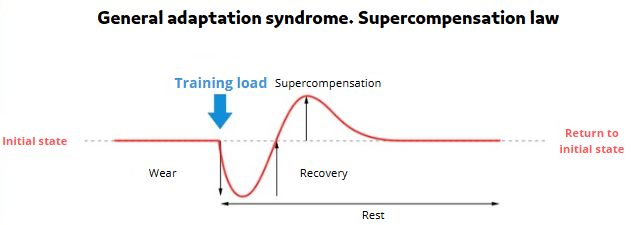

This involves applying one of the basic principles of training, which is the general adaptation syndrome or supercompensation phenomenon, which derives from the stress-recovery-adaptation process defined by Dr. Hans Selye in his law, which says the following: “An organism undergoes a specific set of short-term responses and long-term adaptations after being exposed to an external stressor.” (Dr. Hans Selye; July 4, 1936).

In our context the stressor is lifting weights and the process is as follows:

- Stress is any stimulus that produces a change in the physiological state of the organism. In this case the stress would be doing intense training. Stress affects homeostasis, which is the stable physiological environment that exists within the body.

- La recuperación del suceso de estrés es la forma en que el organismo perpetúa su supervivencia, volviendo a su condición previa al estrés y un poco más, para no volver a sufrir daño en caso de que el estrés vuelva a ocurrir.

- Recovery from the stressful event is the body’s way of perpetuating its survival, returning to its pre-stress condition and then some, so as not to be harmed again in case stress occur again.

- This stress adaptation is the organism’s way of surviving in an environment that subjects organisms to a variety of changing conditions.

In our scenario, stress is produced by the fact of lifting a bar with a considerable weight, which is capable of creating the conditions under which adaptation occurs, that is, a greater capacity to produce force with our muscles. If an organism is subjected to repeated stress, the previous stress produces an accumulation of adaptations that as a result change the appearance and functioning of the organism.

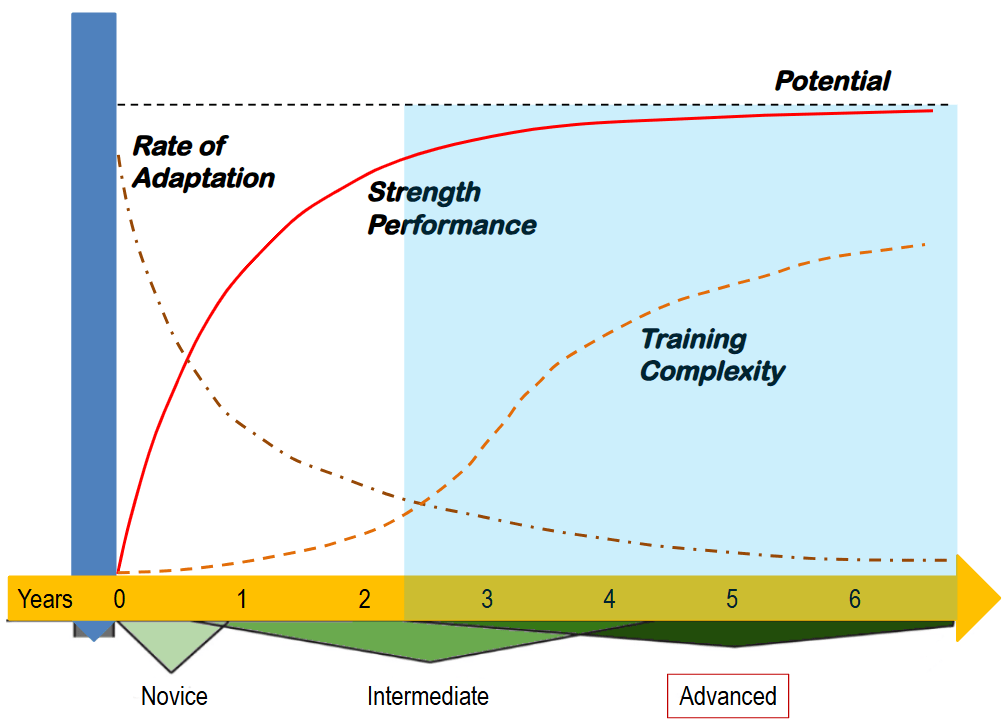

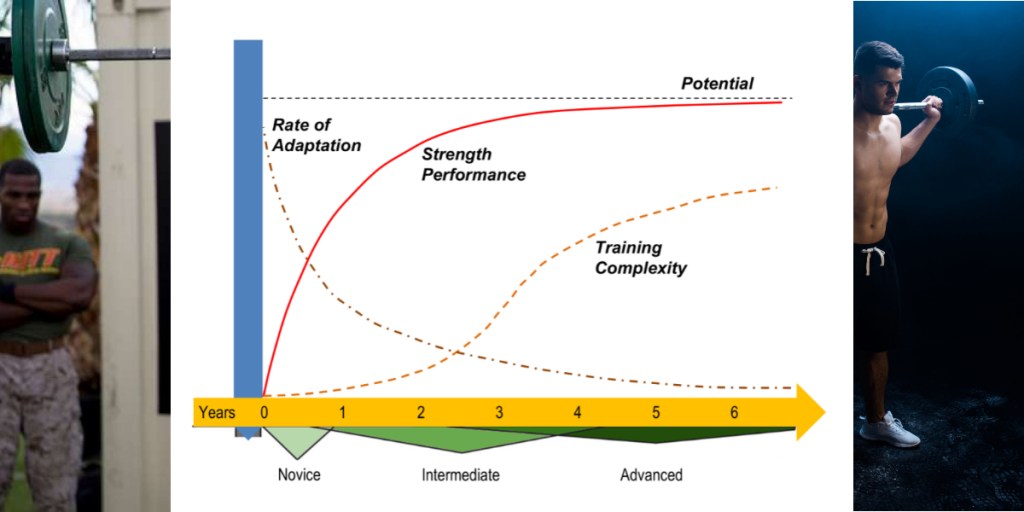

The history of physical stress accumulated as a result of following a training program influences what type of stress we can continue to apply, because the current state of adaptation contributes to an athlete’s ultimate potential to adapt to stress.

Each individual has a limit to their ability to adapt to stress, whether acute stress (short term) or chronic stress (over time). This limit is determined by the genetic endowment and physical condition of an athlete at a given time. And also this limit controls the individual’s potential for athletic performance.

La proximidad de un individuo a este límite determina cuánta mejora potencial le queda por desarrollar en términos de fuerza. Por eso paradójicamente es más fácil volverse más fuerte si aún no eres muy fuerte.

An individual’s proximity to this limit determines how much potential improvement he has left to develop in terms of strength. That’s why it’s paradoxically easier to get stronger if you’re not very strong yet.

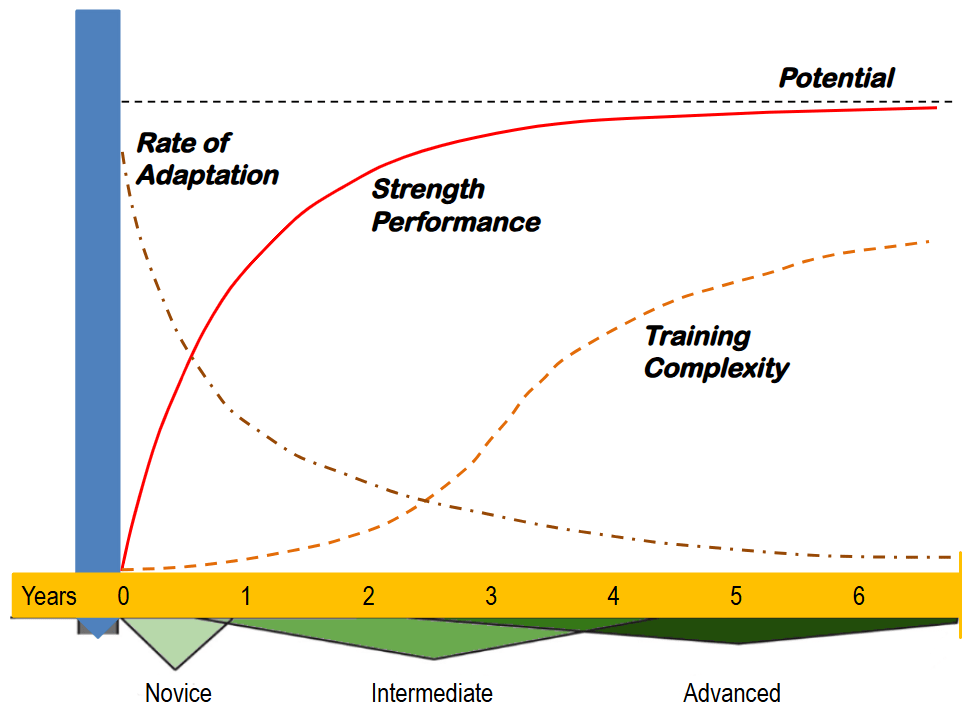

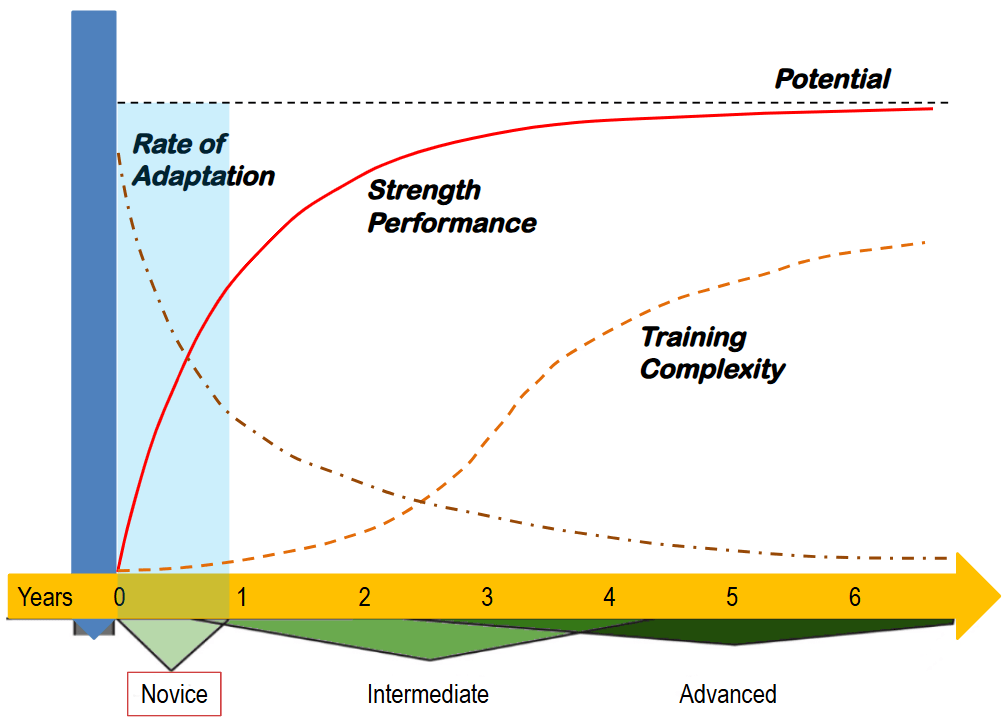

Mark Rippetoe and Andy Baker in their book “Practical Programming for Strength Training (3rd edition)” classify weight lifters as beginners, intermediate and advanced based on the time it takes to recover from a training-induced homeostatic disturbance.

A beginner or novice lifter is someone for whom the stress that is applied during a single training session, together with the recovery from that single stress, is sufficient to cause an adaptation in the next training session. This allows the beginner to add more weight to their effective sets in each training workout for the duration of this beginner phase. The result is a rapid increase in strength in a relatively short period of time. The beginner phase is the stage in an athlete’s strength training history in which the most rapid improvement in strength occurs.

The beginner, due to his inactivity, can progress with training programs that are not specific to the activity of increasing strength with basic exercises with the Olympic bar. This does not happen in the case of intermediate and advanced lifters, where progress in strength depends absolutely on making training programs that are specific.

The best programming to achieve fast, efficient and safe progress in beginners is the linear progression model. This program is characterized because the time needed for recovery after a session and its subsequent adaptation is 48-72 hours. When performing the next workout, they will notice the effects of adaptation by being able to lift a slightly higher weight, but at the same time this greater weight serves to produce new stress at a slightly higher level.

The beginner phase comes to an end in the form of a plateau in performance, when it becomes increasingly difficult to continue progressing from one training workout to the next. This occurs between the third and ninth month of training, with individual variations depending on genetic makeup and those environmental factors that affect recovery. The ever-smaller weight jumps have been depleted, and progress stops despite all efforts to manage recovery.

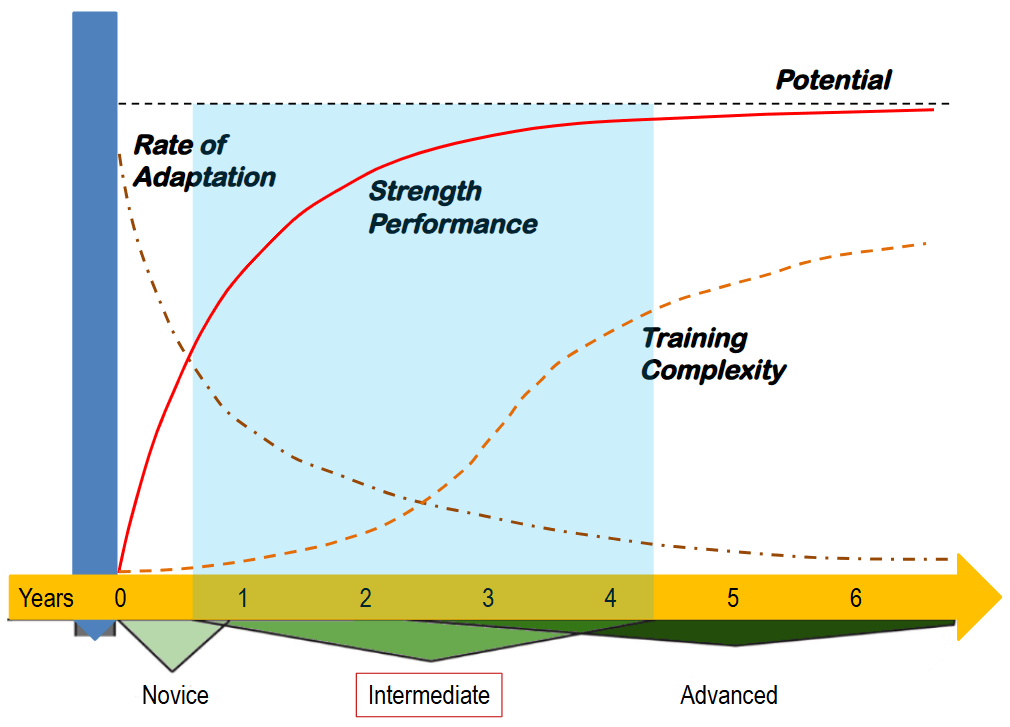

The intermediate lifter needs to handle training weights that are closer to their physical potential to continue improving their strength levels, but their recovery requires a longer period of time. So for adaptation to training to occur, it is better to move to a weekly schedule.

The intermediate lifter faces the following dilemma:

- On the one hand, the ability to apply high-intensity stress to the body is demanded.

- But at the same time the stress required to disrupt homeostasis begins to exceed the ability to recover within the 48-72 hour time period that until then was needed during the beginner phase.

To allow for sufficient stress and sufficient recovery, the training weight must vary over a longer period of time, and for this the training is organized over the period of one week.

The key to achieving success at this stage is to balance these two important and opposing phenomena: the increased need for stress and the required increase in recovery time. Arranging training weights weekly facilitates recovery after one or more more intense training sessions within a single loading period.

Intermediate lifters benefit from exposure to a greater number of exercises than beginners, so they develop new movement patterns.

The end of the intermediate phase of training is marked by a plateau in performance in which the weekly organization of training becomes increasingly difficult to sustain. This can occur in as little as two years, but also four years or more, depending on the individual’s tolerance and level of adherence to progressive training throughout the year.

Virtually all strength training for athletes who do not compete in barbell sports can be accomplished up to the intermediate stage. These athletes not only train in the weight room, but also demand much of their training in their primary competitive sport. This obviously prolongs the duration of this stage to the point that even the most successful athletes will probably never exhaust the benefits of intermediate level strength programming.

The most popular intermediate level program is the Texas method. Other representatives are the Starr model and split routine models such as the 4-day Texas method or the Nebraska model.

Advanced lifters are those who are close to their maximum physical potentials. It corresponds almost exclusively to competitors in the sports of powerlifting and weightlifting.

The level of training volume and intensity is very demanding and requires longer recovery periods than the training weights of the intermediate period. Weight and recovery parameters must be applied in more complex and variable ways, and over longer periods of time. The weighting and recovery periods required for successful progress vary in length from one month to several months.

At this stage the average slope of the improvement curve is very shallow, approaching very close to maximum physical potential at a very slow rate, and fairly large amounts of training effort will be expended for fairly small amounts of improvement.

The number of exercises used is usually less than at the intermediate level. The reason is because exposure to new movement patterns and types of stress is not required, as you have already achieved specialization and adaptation to those that are specific to your particular sport.

Unlike beginners or intermediates, advanced lifters need large amounts of intense work to disrupt homeostasis and force adaptation. This brings the stress required for progress gets closer and closer to the maximum tolerable workload the body can produce and then recover from. For example, an advanced athlete who achieves progression by doing ten sets of squats may not progress if he does nine sets and may overtrain by doing eleven. The window for progress is extremely small.

The most popular advanced program is the pyramid model, followed by the two steps forward, one step back model.

“It never gets easier. You just get stronger.”

Mark Rippetoe

“If you learn nothing else from training, it´s very important to learn that your limits are seldom where you think they are.”

Bibliographic references:

Leave a comment