Learn the surprising science behind why your speed training may actually be holding you back from running faster and reaching your full potential. While many athletes and coaches believe that all out sprinting is the key to maximum speed, it turns out thatthis approach can lock an athlete in to a set speed and prevent them from getting any faster. Of course you need to train max velocity with all out sprinting, 30 flys, etc. However if you really want to achieve your true max speed you need to incorporate other training methods that force the body to adapt and become faster.

We explore the concept of progressive overload, which is the idea that in order to improve your speed, you must challenge your body to work harder and push beyond its current limits. However, this approach can be limited by what is known as the “speed barrier”, a phenomenon where an athlete’s speed fails to increase despite their training age. One effective way to break through this barrier is through the use of floating sprints or ins & outs. This technique involves running at a high intensity, followed by a period where the athlete “floats” and then finishes with an all out sprint. This method allows for:

- A higher top speed.

- Better coordination between the flexors and extensors.

- The development of relaxed sprinting.

We discuss the science behind floating sprints and how they can be used to rewire the nervous system and train the mind and body to break through pattern-built barriers. While floating sprints are an advanced drill that should be introduced carefully, when used properly, they can deliver serious results and help athletes reach their full speed potential.

What if your speed training was actually preventing you from running faster and reaching your true max speed? While it might seem surprising, turns out that all out sprinting over and over again might not make you any faster. If you have your athlete run 30 meters, or 40 meters or 50 meters, sprinting all out all the time, it’s been proven that will not help him develop their speed. That will help him remember their speed. You’re basically making them record their speed and repeat the same speed every single time.

To continually progress and improve your speed, you need to challenge your body to work harder and push beyond its current limits. This idea is commonly referred to as progressive overload. You put in the work, you get the results. Seems pretty obvious. But what happens when despite all that hard work, you’re just not getting any faster. You may have just hit the speed barrier.

The term was first coined by the famed Russian sports scientist Nikolay Ozolin. The premise is that an athlete’s speed should continually increase with their training age. But most of the time this doesn’t happen and the reason why is incorrect training.

When you just sprint hard over and over again, you develop what Oslin called dynamic movement stereotypes, which means you’ve trained your mind and nervous system to lock in your current speed, and no matter how hard you try. You’re simply unable to move your limbs any faster. This is especially true when it comes to max velocity sprinting.

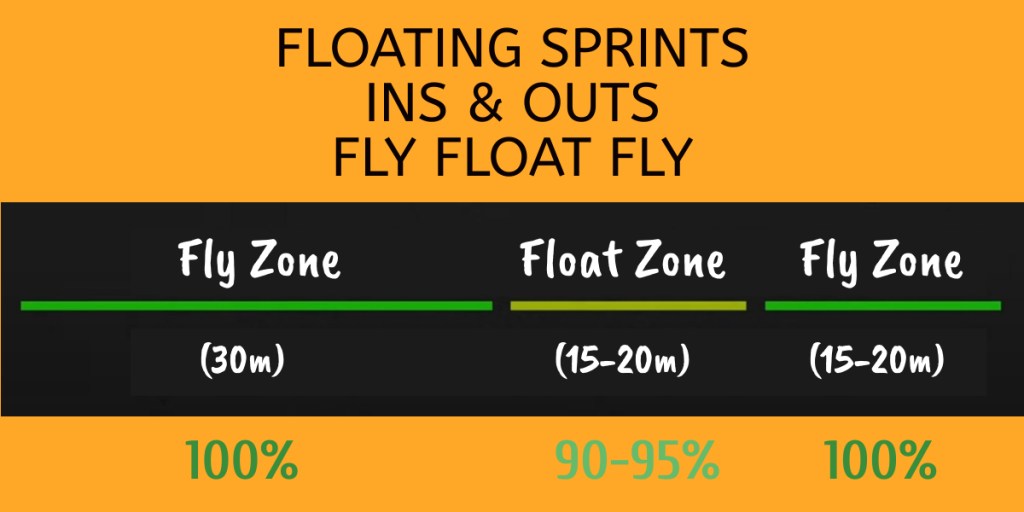

So how do you break your speed barrier or prevent it from happening in the first place? New exercises and intensities that force the body and mind to adapt and become faster. Training like hill sprints, resistant sprints, sprinting specific plyometrics… They’re all great. But when it comes to max velocity, one of the best ways to improve your top speed is with floating sprints or ins & outs, also known as fly float fly. While there are many variations, this is fundamentally how they work:

- Start with a hard 30 meter acceleration. This should be at or very close to all out. This is your first fly zone.

- Next you float for 15 to 20 meters. The force production drops to 90 to 95% but technique and turnover are maintained. The goal here is relax sprinting with great technique.

- The final phase is an all-out sprint for 15 to 20 meters.

There are three substantial benefits that floating sprints provide:

- First they help you hit a higher top speed. Most athletes will be able to go beyond their current top speed during the second sprint or fly zone. This is due to the potentiating nature of the float zone.

- The second benefit is better coordination between the flexors and extensors. The flexors are the muscles that raise your leg. The extensors push it down to the ground. Developing precise timing and coordination between these muscle groups has been proven to increase speed.

- And finally they help develop relaxed sprinting. The float phase is fantastic at developing the ability to run fast with great technique while staying relaxed. This is an essential skill for finishing races strong without chopping your steps.

So floating sprints are a very powerful training tool that taxes the body and the nervous system. They’re an advanced drill that shouldn’t be introduced too early in the season or before an athlete’s ready. But when used properly, they can deliver serious results.

A lot of research shows that by doing in and out sprints, the coordination between the flexors (the muscles that get your knee up) and the extensors (the muscles that put your leg down) increases and thus the limb movement increases and your velocity will increase. It’s a great exercise if you´ve learned how to do it the right way. We have three zones. The first zone the athlete will start from a 3 point start pushing and accelerating as if he’s coming out of the blocks. Once he gets to the first cone he’s gonna try to maintain turnover and reducing the power output. That’s his float zone or the out zone. Then he’s gonna go in again, which is the sprint zone, in the last 15 meters by actually applying more force to the ground and hammering harder with his arms. So drive sprint-float-sprint or in-out-in. This great exercise is done probably the second half of the specific preparation, once the technical model is established to truly develop speed.

Bibliographic references:

- Outperform. (2023). The Surprising Science Proven To Make You Run Faster [Video file]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/3XAewCniWkk?si=D7bVUCk2ZYONh_z-

Leave a comment