Post-activation potentiation (PAP) is a phenomenon whereby an increase in muscle performance occurs after having performed a conditioning activity that elicits a maximum voluntary contraction, a tetanic contraction, or a series of nerve impulses. The physiological mechanisms that originate this phenomenon remain unknown at present. However, two possible hypotheses are considered:

- Phosphorylation of myosin light chains. This causes the interaction between actin and myosin to become more sensitive to the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This occurs to a greater degree in type II fibers.

- Increase in the excitability of motor neurons, which is manifested in the amplitude of the H reflex*. This increase in excitability consists of the increase in the recruitment in quantity and size of the motor units.

* The H or Hoffman reflex is the electrical equivalent of the myotatic reflex.

This phenomenon is most evident in fast motor neurons, so explosive tasks performed after PAP will benefit most from it. Thus, jumping performance is enhanced when PAP occurs. It is worth mentioning that this phenomenon has also sparked interest in endurance activities.

The ideal stimulus that allows triggering PAP in skeletal muscle can be obtained in several ways and based on this the following issues must be taken into account:

- The level of prior contractile activity, to obtain the maximum PAP with the least fatigue. Both factors occur at the same time, so they must be managed correctly to avoid interference.

- The optimal rest time between pre-conditioning activity and explosive strength effort. It has been observed that maximum force production is achieved in the interval of 7 to 10 minutes after conditioning, and with respect to jump performance, the optimal range is between 8 and 12 minutes.

- The biological variability that exists between individuals, and which is due to factors such as muscle fiber type composition and training status.

The types of exercises needed to trigger PAP include:

- Strength exercises, such as squats. Intensity greater than 80% of 1RM or between 3-5 RM. 1-3 sets of 3-5 reps.

- Explosive strength exercises such as weightlifting derivatives (at an intensity greater than 70% of 1RM), plyometrics, and extensive interval exercises (e.g., resisted sled sprints). 1-6 sets. No more than 6 reps per set. Multiple-set workouts are more effective than single-set workouts.

- Dynamic stretching exercises, with a total duration of 5-10 minutes for the protocol.

The improvement in jumping ability is achieved after a rest of 1-9 minutes following the application of the activity that stimulates the PAP. To control the intensity of the training load, it may be interesting to use the OMNI scale of perceived effort in order to avoid an increase in fatigue.

An example of a task to achieve PAP is what sprinters do in speed sessions. Both the running technique and low-intensity plyometric drills performed during the specific warm-up phase help to condition and activate the nervous system to prepare for the high-intensity efforts that the athlete will perform next. Also the typical ankle-bouncing jumps performed before a sprint contribute to awakening this phenomenon for the race.

One of the ways to achieve the PAP effect is through the French contrast method, which is nothing more than the combination of complex training and contrast training. The French trainer Gilles Cometti was the one who proposed this method. However, Dietz modified it by incorporating the combination of complex and contrast training, resulting in better performance in athletes. Before continuing with the French contrast method, we must understand what each of the two types of training that constitute it is about:

- Complex training is based on performing exercises with high or almost maximum intensity weights or resistances followed by plyometric exercises.

- Contrast training consists of performing exercises with high weights followed immediately by explosive exercises. Both maximum strength and explosive strength exercises share the same movement pattern.

The French contrast method consists of performing the following sequence of 4 exercises:

- Compound exercise with high weights

- Plyometric drill

- Plyometric drill with weights

- Assisted or accelerated plyometric drill

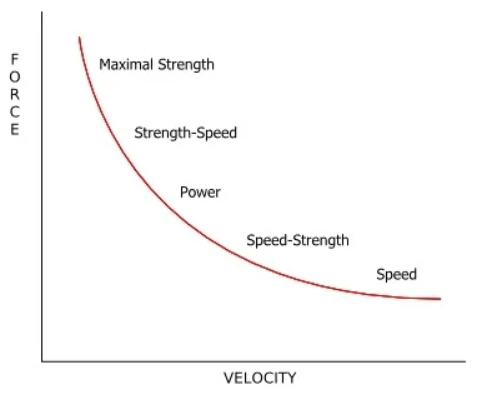

The objective of the French contrast method is to ensure that any athlete who practices it works along the entire force-velocity curve. In this way, we ensure the achievement of both acute and chronic adaptations.

The effect of the French contrast method has been corroborated in more than one scientific study. Here are two examples:

- Naglaa et al. (2019) observed that after 8 weeks of this training in ten triple jumpers, improvements were achieved in both explosive strength and different kinematic parameters of the triple jump.

- Gotás et al. (2016) used complex training to try to produce PAP in 31 athletes from three sports: basketball, athletics throws and luge. After its implementation, increased levels of explosive strength were evident. In addition, they concluded that the appropriate load for the conditioning activity is between 75 and 90% of the 1RM.

And when is it justified to apply the French contrast method? In the following circumstances:

- In sports that require high levels of force and power production in a short period of time, as occurs in team sports, combat sports or track and field.

- After the warm-up as a conditioning activity to acutely enhance the lower body’s force and power production in the following session.

- In athletes with little preparation time to improve lower body strength and power, just like in team sports, since they compete every week.

- In situations where the level of the athletes is not very high, it has been observed that with the French contrast method, superior effects are achieved in each of its sets compared to those obtained through traditional potentiation.

Below are three examples of programming using the French contrast method. The first two are focused on the lower body and the third on the upper body.

- Example 1, for the aim of improving vertical jump ability.

- ¼ isometric squat (85% 1RM 3’’).

- 3 x drop jumps 20 in.

- 3 x ½ squat 50% body weight.

- 3 x jumps over hurdles (hurdle height: 20 in. Distance between hurdles: 1.5 m).

- 3 sets; Rest 20’’ between exercises; Recovery 5′ between sets.

- Example 2, for the aim of improving vertical jump ability.

- ½ squat (3 reps 85% 1RM).

- CMJ (3 reps).

- Trap bar jumps (3 reps 30% 1RM).

- Band assisted jumps (4 reps).

- 3 sets; Rest 10’’ between exercises; Recovery 5′ between sets.

- Example 3, for the purpose of improving launching ability.

- Bench press (3 reps 85% 1RM).

- Plyometric push-ups (3 reps).

- Medicine ball throw (3 reps 30% 1RM).

- Assisted plyometric push-ups with elastic band (4 reps).

- 3 sets; Rest 20’’ between exercises; Recovery 5′ between sets.

Finally, it should be noted that one of the possible reasons why dynamic stretching produces an increase in muscular performance is that it could provoke the PAP phenomenon, obtaining an increase in the excitation of the neuromuscular system. However, further research is needed to confirm this.

Bibliographic references:

- Sale D. G. (2002). Postactivation potentiation: role in human performance. Exercise and sport sciences reviews, 30(3), 138–143. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003677-200207000-00008

- Hodgson M., Docherty D. & Robbins D. (2005). Post-Activation Potentiation. Sports Med 35, 585–595 (2005). https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200535070-00004

- Cerrato M., Bonell C. & Tabernig C. (2005). Factores que afectan el reflejo de Hoffmann en su uso como herramienta de exploración neurofisiológica. Revista de Neurología, 41 (06), 354-360. https://doi.org/10.33588/rn.4106.2004480

- Hernández-Preciado J. A., Baz E., Balsalobre-Fernández C., Marchante D. & Santos-Concejero, J. (2018). Potentiation Effects of the French Contrast Method on Vertical Jumping Ability. Journal of strength and conditioning research, 32(7), 1909–1914. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002437

- Docherty D. & Hodgson M. J. (2007). The application of postactivation potentiation to elite sport. International journal of sports physiology and performance, 2(4), 439–444. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2.4.439

- Picón-Martínez M., Chulvi-Medrano I., Cortell-Tormo J. M. & Cardozo, L. A. (2019). La potenciación post-activación en el salto vertical: una revisión (Post-activation potentiation in vertical jump: a review). Retos, 36, 44–51. https://doi.org/10.47197/retos.v36i36.66814

- Welch M. L., Lopatofsky E. T., Morris J. R. & Taber, C. B. (2019). Effects of the French Contrast Method on Maximum Strength and Vertical Jumping Performance. Paper presented at the 14th Annual Coaching and Sport Science College, East Tennessee State University.

- Elbadry N., Hamza A., Pietraszewski P., Alexe D. I. & Lupu G. (2019). Effect of the French Contrast Method on Explosive Strength and Kinematic Parameters of the Triple Jump Among Female College Athletes. Journal of human kinetics, 69, 225–230. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2019-0047

- Gołaś A., Maszczyk A., Zajac A., Mikołajec K. & Stastny, P. (2016). Optimizing post activation potentiation for explosive activities in competitive sports. Journal of human kinetics, 52(1), 95-106. https://doi.org/10.1515/hukin-2015-0197

Leave a comment