In sprinting form makes function. What does this mean? It means that the sprint technique is highly dependent on the differences in muscular balance between agonist and antagonist muscles.

Kelly Baggett distinguishes in his book “No-Bull Speed Development Manual” two types of runners based on the predominance of one muscle group or another, with its consequent implications in the biomechanics of sprinting.

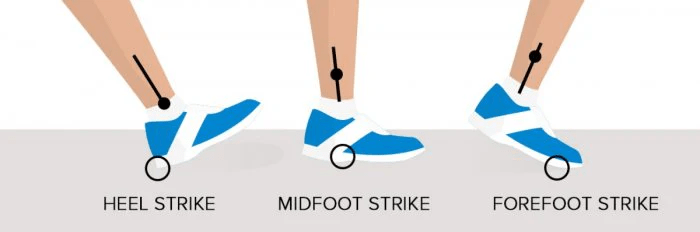

On the one hand, he talks about forefoot runners, who are those in which the main motors of movement are the glutes and hamstrings. These athletes are characterized by having a pleasant, smooth and quiet stride in which the ground contact falls on the metatarsal area of the feet. This support on the metatarsus allows you to take advantage of the stretch-shortening cycle (SCA) that occurs on the Achilles tendon, which stores elastic energy that is returned in the form of reactive force during the return to its initial length; all this translates into being able to make a greater stride length. During the moment of support, little knee flexion is observed, and without the appearance of many bending and pushing. Their foot tends to contact the ground just below their center of gravity, keeping their trunk upright during running at top speed.

On the other hand, the author refers to heel runners, who are those who stand out for having excessively developed quads compared to their hamstrings, or a weak posterior chain compared to the anterior one. Their stride tends to be characterized by being very noisy due to the fact that they impact the ground through the heel, performing a lot of knee flexion and a lot of pushing. This knee flexion and heel support is due to an effort by the athlete to use his quads predominantly stronger than his antagonist muscle group. It should be noted that contact on the heel prevents the Achilles tendon from benefiting from the CEA, which means not being able to perform a large stride length naturally. In addition, these athletes also tend to contact the foot in front of their center of gravity, tilting the trunk forward during the development of the race. Running this way, apart from being ineffective, greatly increases the risk of injury.

Going back to the beginning and remembering that in sprinting form makes function, it is concluded that for technique and function to be optimal, the stride in sprinting must be posterior chain dominant. That is, the glutes and hamstrings, along with the paravertebral muscles and the back muscles, must predominate over the muscles of the front part of the body to allow the stride to be performed with the hip as the main joint of movement and with the metatarsus as a support point for the foot on the ground, as opposed to the knee and heel respectively. Only in this way both efficiency and effectiveness in movement will be achieved.

While the majority of the population has a size ratio in the balance between hamstrings and quads of 3:7, in elite sprinters this ratio is 6:4 in favor of the hamstrings, which says a lot about the role that the muscles of the posterior thigh region play during the stride in sprinting.

The same author also makes another classification of runners that is still redundant and overlaps with the previous one: hip runners and knee runners.

- Hip-dominant runners run through contraction of their glutes and hamstrings. Their strides are much softer and quieter and it seems as if they are running on the balls of their feet, that is, they contact the metatarsals.

- Knee-dominant runners have a lot of activation of their quads, flex the knee of their supporting leg a lot, and tend to run on their heels. This causes them to make a lot of noise in their stride.

Once again we must look for the prominence of the hip to achieve both efficiency and effectiveness in the movement of the stride and this will be given by the predominance of a large posterior chain.

With all this, you’re sure to end up asking yourself the following question: “Is it possible that a heel runner can change to be a forefoot runner?” Or what is almost the same: “Is it possible for a predominantly knee runner to become a hip runner?” The answer is yes. It’s all about correcting the muscular imbalances that exist since it is still a postural problem.

The point is that it takes time to make this postural correction and the athlete must also stop competing or even training by doing sprints during that time. All this is because if we start running at top speed while we are correcting our weak links to modify our body at a biomechanical level, we will continue to do it involuntarily with the same technique as always since our brain has it very assimilated and automated from repeating it all our life. It should be noted that when running very fast no one consciously thinks about his running technique and influences it, because otherwise he stops going fast since the athlete loses his focus of thought on this goal. Therefore, we must also re-educate our nervous system through technical assimilation exercises so that new neural connections are formed that make the new way of sprinting come out naturally.

The problem is that many track and field coaches, physical trainers and physical education teachers lack knowledge about kinesiology, biomechanics and postural hygiene, something that from my point of view seems even negligent. This lack of knowledge, together with the belief that talent is always innate and the short-term mentality that so characterizes Western societies, causes already trained athletes to be preferred and time is not invested in wanting to improve those who present postural and technical deficiencies. The lack of desire to investigate the cause of the latter’s problems leads them to believe the fact that they were born this way and will always be that way, without the possibility of changing, which leads to frustration with the more than likely consequent abandonment of sports practice. The result is the loss of athletes who, having corrected their defects, could improve and, even those who know whether to show a lot of talent to stand out, in this case, in sprint races or in other sports in which speed is the most important physical ability to succeed.

Bibliographic references:

- Baggett, K. (2006). The Ultimate No-Bull Speed Development Manual.

- Yessis M. (2013). Explosive Running. Second Edition. Ultimate Athlete Concepts.

- Yessis M. (2006). Build a Better Athlete: What’s Wrong with American Sports and How to Fix It. Ultimate Athlete Concepts.

- Yessis M. (2006). Sports: Is it All B.S.?: Dr Yessis Blows the Whistle on Player Development. Ultimate Athlete Concepts.

Leave a comment