According to Dr. Ken Clark, every step you sprint from acceleration all the way through the end of a 100 meters or 200 meters, or you name it, you need to apply enough vertical impulse. Impulse is the product of force and time. It’s force applied for a period of time. You need to apply enough vertical impulse to support your body weight, so you don’t crash, and to lift your center of mass (COM) into the next step.

So you need to apply enough vertical impulse to support your bodyweight over the course of a step (of a contact and a flight time). So as you run faster, the contact times get shorter and shorter, and they are briefer and briefer. You have less time to apply force. That means as the contact times get shorter and shorter, the force has to get bigger and bigger. The amount of vertical force you apply with every step gets bigger and bigger. Likewise if you take two athletes and everything else being equal, the guy who’s faster applies more vertical force than the guy who’s slower. So we can summarize it like this:

Shorter contact time → More vertical force → Faster speed

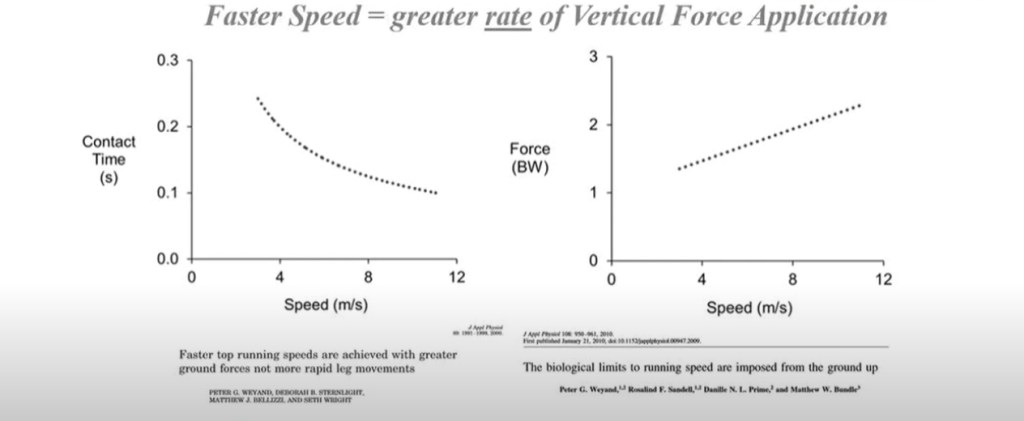

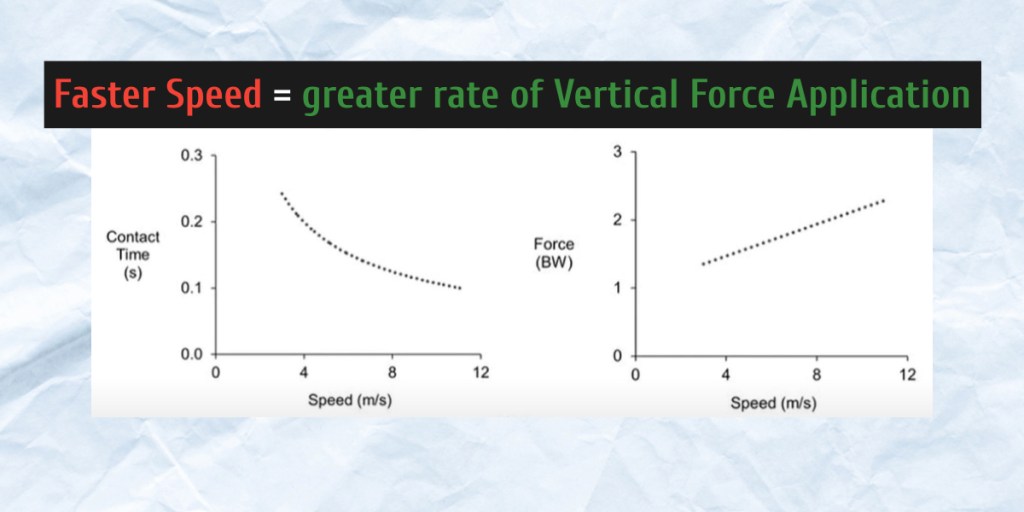

To studies from Dr. Peter Weyand basically established this conceptually. We see on a graph on the left speed in meters per second. Everything from a slow jog all the way up to an elite level sprint shorter ground contact times. On the right we see vertical force normalized to units of body weight. If you weigh 200 pounds which sadly you do one body weight is 200 pounds, two body weights is 400 pounds and three body weights is 600 pounds. This is a little bit of a simplification but you get the idea.

Faster speeds it’s not just more force. It’s a greater rate of force application: more force applied faster. For those of you that do some strength and conditioning work, that doesn’t come as a surprise. The stimulus you’re chasing isn’t just strength per se. Most of the time it’s rate of force application because that’s what’s transfers to athletic performance.

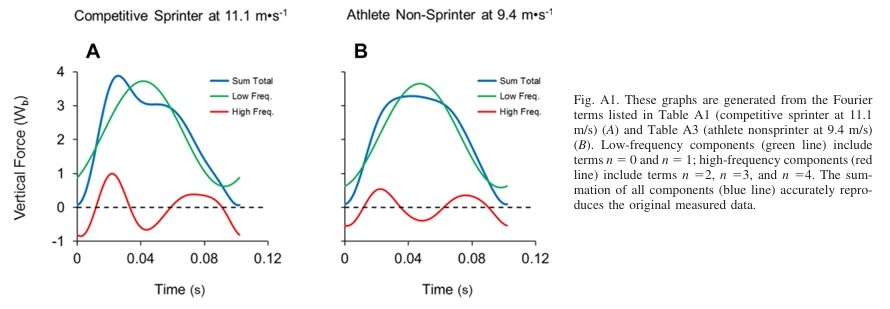

If we look at what’s happening with every step, and we look at a competitive sprinter who can reach 11 meters per second (over 24 miles an hour) versus a team sport athlete (an athletic non-sprinter), we can observe these two graphs. We look at the vertical forces on the y-axis normalized to weight of the body or body weights, and we have contact time on the x-axis. What’s interesting is it’s what’s going on in the second half of ground contact in a vertical direction. This is different in a horizontal direction, but in the vertical direction the second half of ground contact is no different between those that are team sport athletes and of average speed versus those that are elite sprinters and really fast. So what’s going on from the middle to the end in the push is not much different. But what’s going on during the first part of ground contact is very different. People who are faster apply more force in the first half of ground contact time than people who are not as fast. Again, this rate of force application is the difference between being really fast and not as fast. The difference in that rate of force application is in how they’re striking the ground (strike mechanics).

Bibliographic references:

- Holler T. [Coach Tony Holler]. (2022). Ground Contact Time and Vertical Force

[Video]. Recovered from https://youtu.be/Um2l6x4gzl8?si=EAd3ROqkyPw9-pok - Weyand, P. G., Sternlight, D. B., Bellizzi, M. J., & Wright, S. (2000). Faster top running speeds are achieved with greater ground forces not more rapid leg movements. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 89(5), 1991–1999. https://doi.org/10.1152/jappl.2000.89.5.1991

- Weyand, P. G., Sandell, R. F., Prime, D. N., & Bundle, M. W. (2010). The biological limits to running speed are imposed from the ground up. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 108(4), 950–961. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00947.2009

- Clark, K. P., & Weyand, P. G. (2014). Are running speeds maximized with simple-spring stance mechanics?. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 117(6), 604–615. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00174.2014

Leave a comment